Publications

September 15, 2021

The Nortel Saga- A Tale of Two Cities

The Nortel Saga-A Tale of Two Cities1

By The Honourable Frank J.C. Newbould, K.C.2

The Nortel Networks Corporation saga was unique for the parties, the lawyers and the judges. Judge Gross of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Delaware and I presided over the case in a joint trial that had never occurred before.3.

Nortel Networks Corporation (“NNC”) was a publicly-traded Canadian company and the direct or indirect parent of more than 140 subsidiaries located in more than 100 countries, collectively known as Nortel, which operated a global networking solutions and telecommunications business. It carried on business in Canada, where the head office was located, and through subsidiaries in the United States, the EMEA region, as well as the Caribbean and Latin America and Asia.

On January 14, 2009, the Canadian companies filed in Toronto under the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act (“CCAA”). In the United States, most of the U.S. incorporated entities filed in Wilmington, Delaware under chapter 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. On the same day the principal UK subsidiary of Nortel, and certain of their EMEA subsidiaries save the French subsidiary Nortel Networks S.A. (“NNSA”), were granted administration orders under the UK Insolvency Act, 1986. Neither the Canadian nor the US debtors sough recognition orders in the UK. On the following day, a liquidator of NNSA was appointed in France pursuant to Article 27 of the European Union’s Council Regulation (EC) No 1346/2000 on Insolvency Proceedings in the Republic of France.

At the outset of the insolvency, the Nortel debtors had hoped to restructure their profitable lines of business, but by June, 2009 it was determined that this would not be possible. Steps were taken to sell the assets, which consisted of a number of profitable lines of business and residual intellectual property consisting primarily of patents and patent applications. Nortel sold its business lines, including the IP needed for each business line, for approximately US$3.285 from mid-2009 through to March 2011. In April 2011 it entered into a stalking horse bid agreement with Google for US$900 million, but an auction in June, 2011 sold the residual patent portfolio to an entity aptly named Rockstar (Apple, Microsoft, Ericsson, Blackberry, Sony and EMC) for US$4.5 billion. From these sales, US$7.3 billion was escrowed and available for the creditors of the Nortel debtors.

The joint trial was before the days of Zoom. The court rooms in Toronto and Wilmington were set up electronically. Each day of the trial there were 30 to 40 lawyers in each courtroom. The lawyers and witnesses could and did appear in either courtroom and communicate with a lawyer, witness or the judge in the other courtroom through state of the art telecommunications services that were created for the trial at great expense. On some occasions a lawyer in one courtroom cross-examined a witness in the other courtroom. It worked seamlessly and well. The trial ran intermittently from May 12 to September 23, 2014.

The issue for the joint trial was how the escrowed sales proceeds from the sale of the Nortel assets of US$7.3 billion were to be allocated amongst the Nortel debtors. The represented parties included the Canadian debtors, the US debtors, the UK Pension Claimants, the EMEA debtors, bondholders and various creditor committees.

One may well ask how it was that these different creditor groups came to be parties to a procedure that required a Canadian and US judge decide for all the Nortel debtors that participated. The answer goes back to early days in the insolvency process. When the decision to sell Nortel assets was made in June, 2009, the parties realized that a large portion of the assets to be sold consisted of intellectual property that would decline in value with age. If determining the allocation of proceeds from Nortel’s assets were a precondition to their sale, sales would be substantially delayed, and the value of the assets would depreciate, resulting in less money for all creditors. Avoiding a dispute during the sale process about how to allocate the proceeds allowed the parties to obtain the highest monetary value for the assets being sold. It was a wise decision, as once the sales concluded, there was no agreement of the parties and it took several years until 2017 to reach a final conclusion.

Accordingly, in June, 2009 an agreement called an Interim Funding and Settlement Agreement (IFSA) was signed by 38 Nortel debtor entities in Canada, the U.S. and EMEA. It provided for certain funding for the Canadian debtors by the US debtors. It also provided that the Nortel assets would be sold and the proceeds put into escrow. The parties agreed to negotiate in good faith and attempt to reach agreement on a timely basis on a protocol for resolving disputes concerning the allocation of the sale proceeds. However, the parties could not agree on an allocation process and the issue went to both courts.

The UK Administrator and the EMEA debtors argued that the parties had agreed in the IFSA to an enforceable arbitration clause that did not permit the Canadian and US courts to decide on the allocation of the sale proceeds for entities outside of Canada and the US. Both courts held that there was no enforceable arbitration agreement as the obligation to negotiate a protocol was at best an unenforceable agreement to agree. It was also held that in the IFSA, it had been agreed that any proceeding seeking any relief must be commenced in the US and Canadian courts in a joint hearing of both courts under a cross-border protocol, if such proceeding would affect the Canadian, US or EMEA debtors. It was held that the UK Administrator and the EMEA debtors had attorned in the IFSA to the jurisdiction of the US and Canadian courts. Thus the outcome was that the UK Administrator and the EMEA debtors were required to litigate their claims to the escrow funds in the US and Canadian courts in a joint hearing.

Concurrently with the negotiation of the IFSA, the Canadian and US Debtors and certain committees negotiated a Cross-border Insolvency Protocol that received approval of the Canadian and US courts in June 2009. It contained unique provisions that have become commonplace in cross-border protocols involving Canada and US insolvency proceedings. The Protocol contained a number of provisions regarding the independence of the Canadian and US Courts and the exclusive jurisdiction of each Court to determine matters arising in the Canadian and US proceedings respectively. Included in the Protocol were the following provisions:

- The approval and implementation of this Protocol shall not divest nor diminish the U.S. Court’s and the Canadian Court’s respective independent jurisdiction over the subject matter of the U.S. Proceedings and the Canadian Proceedings, respectively.

- The U.S. Court shall have sole and exclusive jurisdiction and power over the conduct of the U.S. Proceedings and the hearing and determination of matters arising in the U.S. Proceedings. The Canadian Court shall have sole and exclusive jurisdiction and power over the conduct of the Canadian Proceedings and the hearing and determination of matters arising in the Canadian Proceedings.

While each court had sole jurisdiction over its proceedings, the Protocol contained a unique provision regarding discussion between the two judges. Included were the following:

- The U.S. Court and the Canadian Court may communicate with one another, with or without counsel present, with respect to any procedural matter relating to the Insolvency Proceedings...

- The U.S. Court and the Canadian Court may conduct joint hearings (each a “Joint Hearing”) with respect to any cross-border matter ...where both the U.S. Court and the Canadian Court consider such a Joint Hearing to be necessary or advisable, or as otherwise provided herein, to, among other things, facilitate or coordinate proper and efficient conduct of the Insolvency Proceedings or the resolution of any particular issue in the Insolvency Proceedings. With respect to any Joint Hearing, unless otherwise ordered, the following procedures will be followed:

The Judge of the U.S. Court and the Justice of the Canadian Court, shall be entitled to communicate with each other during or after any joint hearing, with or without counsel present, for the purposes of (1) determining whether consistent rulings can be made by both Courts; (2) coordinating the terms upon of the Courts’ respective rulings; and (3) addressing any other procedural or administrative matters.

This latter provision was instrumental in Judge Gross and I each being able to come to the same decision on the allocation of the US$7.3 billion.4 It was recognized by all parties that if Judge Gross and I came to different conclusions, it would not be helpful to a successful resolution for the benefit of all parties. In my decision I stated:

Judge Gross in Wilmington and I have communicated with each other in accordance with the Protocol with a view to determining whether consistent rulings can be made by both Courts. We have come to the conclusion that a consistent ruling can and should be made by both Courts. We have come to this conclusion in the exercise of our independent and exclusive jurisdiction in each of our jurisdictions. These insolvency proceedings have now lasted over six years at unimaginable expense and they should if at all possible come to a final resolution. It is in all of the parties’ interests for that to occur. Consistent decisions that we both agree with will facilitate such a resolution.

Judge Gross made similar statements in his decision.

The decision to be made involved a very complex business model that provided great scope to the parties to make drastically different submissions.

The Nortel business was not carried out on jurisdictional lines. Nortel operated along business lines as a highly integrated multinational enterprise with a matrix structure that transcended geographic boundaries and legal entities organized around the world. No single Nortel entity, either the Canadian debtors in Canada, the US debtors in the US or NNUK or any of the other EMEA debtors, was able to provide the full line of Nortel products and services, including R&D capabilities, on a stand-alone basis. R&D was the primary driver of Nortel’s value and profit and it was performed at labs around the world and shared throughout Nortel.

There was no settled law to determine how the sale proceeds should be allocated. The parties differed widely as to the approach to be taken.

The dilemma facing the two Courts was put well by Judge Gross who stated:

There is nothing in the law or facts of this case which weighs in favor of adopting one of the wide ranging approaches of the Debtors. There is no uniform code or international treaty or binding agreement which governs how Nortel is to allocate the Sales Proceeds between the various insolvency estates or subsidiaries spread across the globe.

The main argument of all parties centered on a transfer pricing agreement made by the Nortel entities named Master Research and Development Agreement (“MRDA”). Much time was taken by expert and lay evidence regarding the MRDA and in closing arguments. In the end, it was held to be irrelevant.

Under the MRDA, the parent Canadian company NNL was the legal owner of the Nortel intellectual property and other Nortel entities were granted an exclusive license by NNL to make and sell Nortel products in their territory using or embodying Nortel intellectual property developed by Nortel companies anywhere in the world and a non-exclusive license to do so in territories that were not exclusive to them. What the ownership rights of NNL were and what the license rights were that were granted in the MRDA were highly contested.

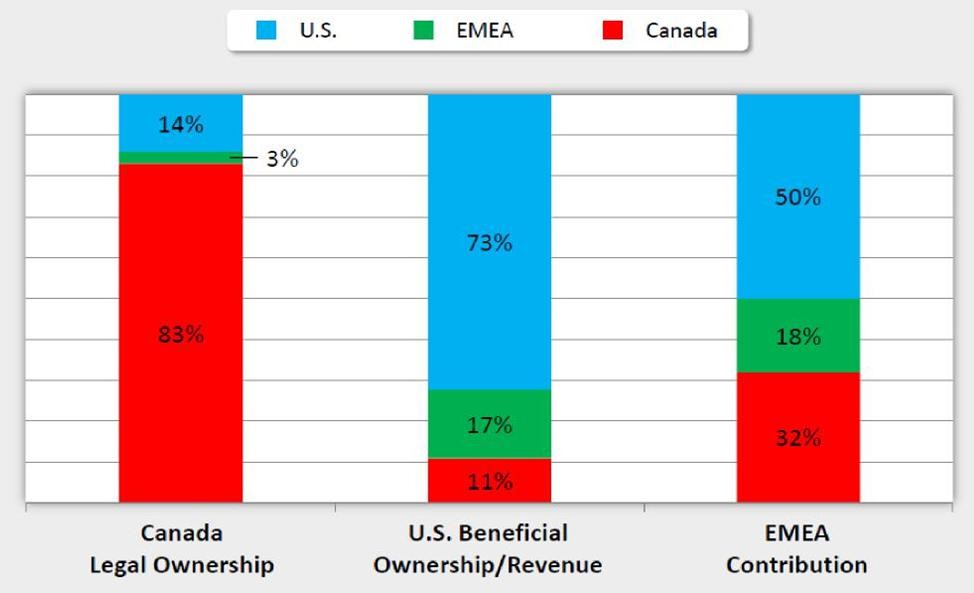

The Canadian debtors argued that under the MRDA, the Canadian parent NNL owned the IP and the interests of the US debtors and the other participants to the MRDA were restricted to certain exclusive and non-exclusive license rights granted to them by NNL that were limited for several reasons in their use and value. They contended for an allocation of US$6.034 billion to the Canadian debtors, US$1.001 billion to the US debtors and US$300.7 million to the EMEA debtors.

The US was the largest market for Nortel products. The US debtors and other US interests argued that they held all of the rights and all of the value in the IP in their respective exclusive territories and that the license rights they held were not subject to the restriction or limitations that the Canadian debtors asserted. They contended that all of the economic value in the IP in the exclusive territory belonged to the licensee and that the legal title held by the Canadian parent NNL in the IP under the MRDA was a purely “bare” legal title with no monetary value. They contended for an allocation of US$.77 billion to the Canadian debtors, US$5.3 billion to the US debtors and US$1.23 billion to the EMEA debtors.

The EMEA debtors had provided substantial funds for R&D and argued that each of the parties to the MRDA jointly owned all of the IP in proportion to their financial contributions to R&D, and that all states should share in the sale proceeds attributable to IP in those same proportions. The joint ownership was said to arise independently of, but recognized in, the MRDA. They contended for an allocation of US$2.32 billion to the Canadian debtors, US$3.636 billion to the US debtors and US$1.325 billion to the EMEA debtors.

The extreme allocation proposals were contained in a chart filed in argument:

Judge Gross and I differed on the interpretation of the rights of the parties under the MRDA, I essentially agreeing with the Canadian debtors’ position and he agreeing with the US debtors’ position. I held that under the MRDA, the Canadian parent NNL had all ownership interests in the Nortel IP subject to non-exclusive licenses to the other parties to make and sell Nortel products, which no buyer of the IP would pay for. Judge Gross held that NNL had no rights to exploit Nortel IP in the US and that the US debtors had the exclusive economic and beneficial ownership pf the Nortel IP in the US. We both held that the MRDA did not provide joint ownership of the IP as contended by the EMEA debtors.

However, we both decided that the MRDA was not applicable to the allocation issue. We both held that the MRDA was an operating agreement and was not intended to, nor did it, deal with the disposal of all of Nortel’s assets in a situation in which no revenue was being earned and no profit or losses were occurring as a result of the insolvency of Nortel. The MDRA was a transfer pricing agreement to deal with the allocation of profits while Nortel operated as a going concern business.

The allocation method each of us chose was a pro rata allocation which we referred to as a modified pro rata allocation. The jurisdiction to do that in Canada was under the CCAA provision in section

11(1) that “a court may make any order it considers appropriate in the circumstances” and common law that as a superior court of general jurisdiction, the Superior Court of Justice has all of the powers that are necessary to do justice between the parties. Except where provided specifically to the contrary, the Court’s jurisdiction is unlimited and unrestricted in substantive law in civil matters. The jurisdiction to decide that in the US was similar. The Bankruptcy Code in section 105(a) permits courts to “issue any order, process, or judgment that is necessary or appropriate to carry out the provisions of [the Code]”. The Third Circuit has construed this provision to give bankruptcy courts “broad authority” to provide appropriate equitable relief to assure the orderly conduct of reorganization proceedings.

What drove this approach was the fundamental tenet of insolvency law that all debts shall be paid pari passu and all unsecured creditors receive equal treatment. The task was to determine the amount to be allocated to each of the Canadian, U.S. and EMEA debtors' estates. We each held that directing a pro rata allocation would constitute an allocation as required and could be achieved by directing an allocation of the escrowed funds to each debtor estate based on the percentage that the claims against that estate bore to the total claims against all of the debtor estates. In simple terms, if for example the Canadian debtor estates had recognized claims that were 10% of all recognized claims for all of the debtor estates in issue, the Canadian estates would receive 10% of the escrowed funds. Once the escrowed funds were allocated, it was up to each Nortel estate acting under the supervision of its presiding court to administer claims in accordance with its applicable law.

It was a modified pro rata allocation as the decisions recognized the rights of each debtor estate to its cash-on-hand, settlements and intercompany claims, one of which resulted in an allowed $2 billion claim of the US subsidiary NNI against the Canadian parent NNL

It was argued by the US interests that a pro rata allocation constituted an impermissible substantive consolidation not permitted by Owens Corning, 419 F. 3d 195 (3d Cir. 2005). However, the funds from the sale of the assets did not belong to any one estate and it could not be said that they constituted separate assets of two or more estates that would be combined. Thus there was no substantive consolidation.

Appeals were taken. In Ontario, leave to appeal was sought from the Ontario Court of Appeal. Leave was denied. In the US, an appeal was taken to the US District Court, and mediation was ordered by District Court Judge Stark. Shortly after the Ontario Court of Appeal refused leave in Ontario, Judge Stark referred the case to the 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals, which had several years earlier been very critical that the case had yet not settled5. Shortly after that referral, the case was settled by mediation in 20176 .

The result was an allocation as follows:

Canada- 57.10% or US$4.1 billion (had claimed US$6.1 billion)

US-24.35% or US$1.8 billion (had claimed US$5.3 billion)

EMEA-18.55% or US$1.3 billion (had claimed US$1.325 billion)

The total costs of the Nortel saga exceeded US$2 billion. The picture that follows is apt.

Or, how creditors fight over the cow and the professionals milk it!

____________________________________________________________________

1 The joint trial was held simultaneously in Toronto, Ontario and Wilmington, Delaware. It was a joint trial of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice (Commercial List) and the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware.

2 Counsel to Thornton Grout Finnigan LLP in Toronto, Canada and associate member of South Square in London, UK

3 At the time I was the Head (team lead) of the Commercial List of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice in Toronto.

4 See Nortel Networks Corporation (Re) 2015 ONSC 2987; 2016 ONCA 332; 532 B.R. 494 (U.S. Bankr. D. Del. 2015).

5 669 F.3d 128 at 143-44 (3rd Cir. 2011).

6 There had been three different mediations prior to the joint trial, none of which were successful.